A parade of sad relations

Artificial intelligence, analogies, falling in love, and Helen Keller

Oh hello, oh hi.

How are you?

Are you doing good?

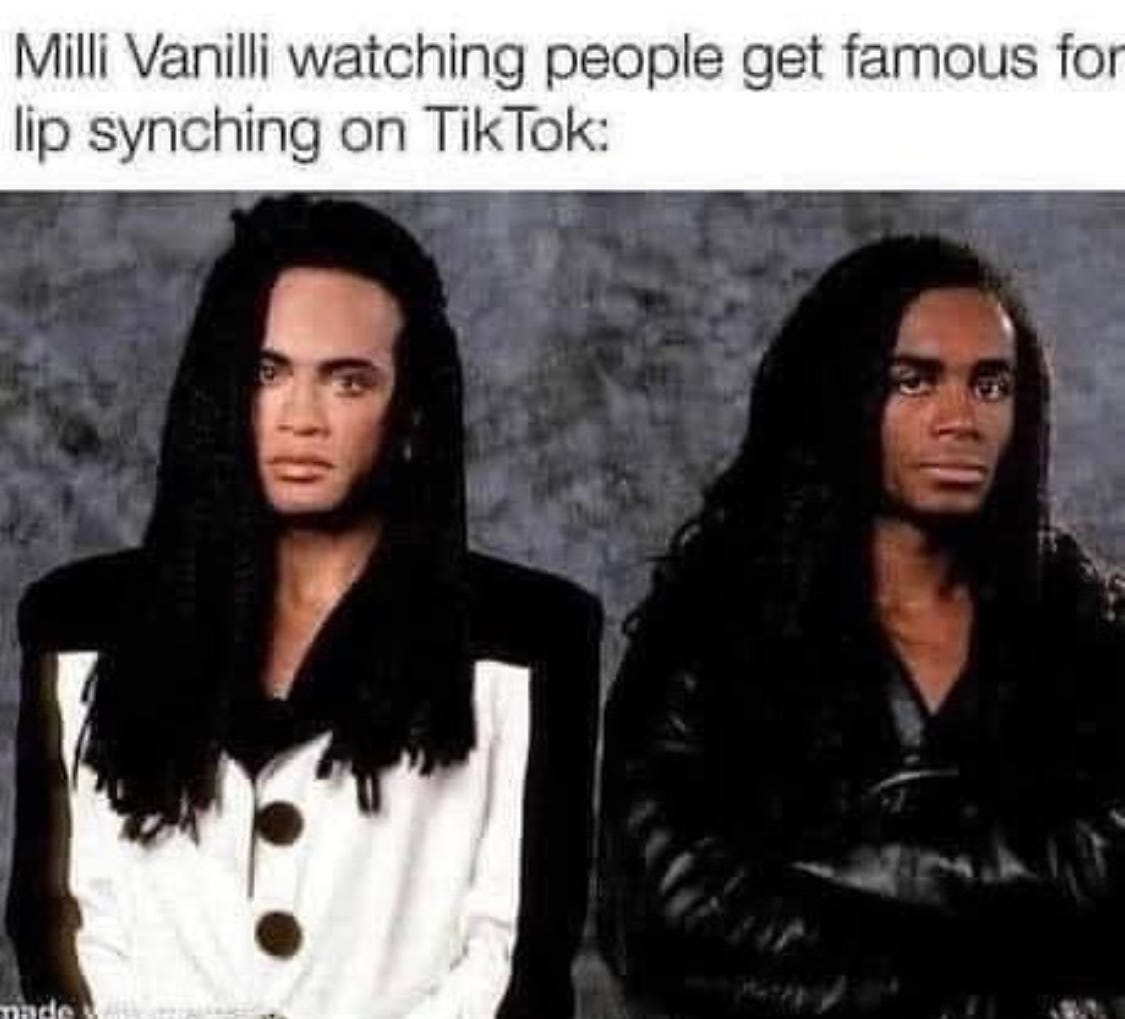

Are you doing better than Rob and Fab?

So many things happening, lately.

My friend with the coolest name®

Van Veen came to visit on her way to the Ladies Who Strategize retreat. We saw some art and had some ice cream.Then my Phish-following friend ® Jeff Miller stopped by for a few days. We ate tacos and vis…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Delightful to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.